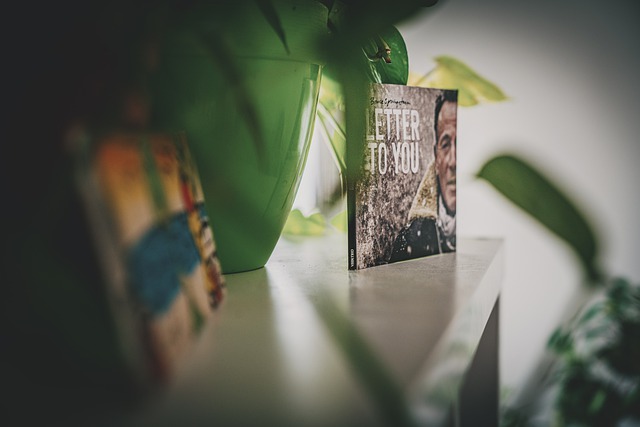

Finding His Religion

With Devils & Dust Bruce Springsteen rediscovers his Catholic roots

by Maurice Timothy Reidy

Finding His Religion

With Devils & Dust Bruce Springsteen rediscovers his Catholic roots

by Maurice Timothy Reidy

Is

Bruce Springsteen a Catholic songwriter? There’s a strong argument to

be made that he is. Catholic images can be found on many of his albums,

especially his early ones, and at times he seems obsessed with the

search for redemption, a favorite theme for Catholic artists from

Caravaggio to Graham Greene. But Springsteen’s albums have rarely been

explicitly religious, and he has admitted in interviews that he has

tried to keep his childhood faith at a distance.

That is until Devils & Dust. Devils

is Springsteen’s most religious album to date. It reflects the concerns

and anxieties of a man who, as he has grown older, has started asking

the big questions that faith promises answers to. What’s surprising is

that his faith has strengthened the songs, not weakened them. Usually

when a songwriter sings about Jesus it’s a sure sign that he’s jumped

the shark. But Springsteen is best when he writes about what he knows,

and faith has allowed him to enter into the lives of his characters,

giving his songs an empathetic power that others have lacked.

Springsteen spoke about his Catholic faith, and how it influenced his latest album, in a recent interview with the New York Times.

“I’m not a churchgoer,” he said, “but I realized, as time passes, that

my music is filled with Catholic imagery. It’s not a negative thing.

There was a powerful world of potent imagery that became alive and

vital and vibrant, and was both very frightening and held out the

promise of ecstasies and paradise. There was this incredible internal

landscape that they created in you….As I got older, I got a lot less

defensive about it. I thought, I’ve inherited this particular landscape

and I can build it into something of my own.”

Reviews of Devils & Dust have compared it to The Ghost of Tom Joad, another pared-down, acoustic album in which Springsteen inhabited a series of depressed, downtrodden characters. Yet Devils is a better album, largely because it is built on the “inherited landscape” of faith. Tom Joad

was a noble effort, but it didn’t work as an album. As Stephen Metcalf

recently pointed out on Slate, the record is a “little distant in its

sympathies, as if Springsteen had thumbed through back issues of The Utne Reader before sitting down to compose.”

Though a number of the songs were written at the same time as Joad, and are similarly “distant in their sympathies” Devils & Dust

does not suffer from its predecessor’s studied reportorial approach. On

songs like the title track, faith has given Springsteen a new

dimension?he can explore?with?his characters, in this case a soldier

confronting the evils of war. “I got God on my side,” he sings. “I’m

just trying to survive / What if what you do to survive / Kills the

things you love.” On Long Time Coming he sings of a father who prays that he’ll raise his kids right, and that their “sins” would be their own.

And then there’s Jesus Was an Only Son,

the best song on the album and the best piece of religious music I’ve

heard in years. The song, which tells of Jesus’s relationship with

Mary, made me think about what it must have been like to live in the

Renaissance, when the best artists of the day brought their talent to

bear on the Gospel. Springsteen’s song is not only wonderfully melodic,

it is theologically profound. “Well Jesus kissed his mother’s hands /

Whispered, “Mother, still your tears. For remember the soul of the

universe / Willed a world and it appeared.”???????

“You have to be constantly writing from your own inner core.” Springsteen says on the DVD on the flip side of Devils & Dust.?

“Whether in New York City, Jersey shore, or set out West, you’re still

writing from the essential core of who you are. That has to be a place

in every song or the song dies.” As Springsteen has grown older, he has

had to find new and creative ways to connect with the lives of his

characters. He’s now a multimillionaire, living on a horse farm in

Jersey; it’s hard for him to sing about kids living in the South Bronx

without sounding woefully inauthentic, if not phony. Fortunately for

listeners though, his inescapable Catholicity has provided him a

language with which he can connect with the other members of the body

of Christ.?

Maurice Timothy Reidy is an associate editor at Commonweal magazine.

Comments to: [email protected]